Learning Styles and Preferences Analysis: A Retrospective

Education is a deeply personal journey, one that is shaped by a multitude of factors. One such factor that has garnered significant attention over the years is the concept of learning styles and preferences. The idea behind this theory is that individuals have unique approaches to acquiring and processing information, based on their innate tendencies and inclinations. While it may seem intuitive to tailor education to these individual preferences, recent research suggests a more nuanced understanding of how learning styles impact educational outcomes.

The concept of learning styles gained prominence in the 1970s with the work of psychologists like David Kolb and Howard Gardner. Kolb proposed his experiential learning model, which identified four different learning styles: converging, diverging, assimilating, and accommodating. These four categories were based on two dimensions – active/reflective observation and abstract/concrete conceptualization.

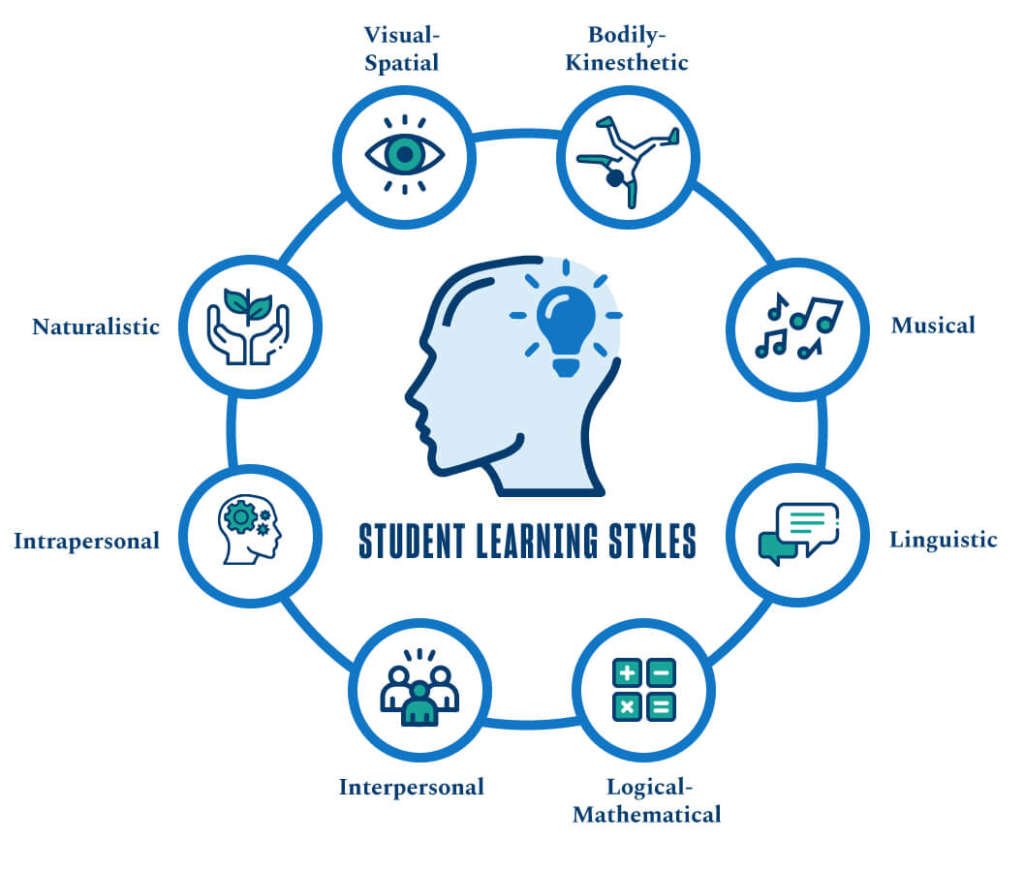

Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences further expanded the notion of individual differences in learning preferences. He posited that there are eight distinct types of intelligence – linguistic, logical-mathematical, musical-rhythmic, bodily-kinesthetic, spatial-visual, interpersonal, intrapersonal, and naturalistic – each representing a different way learners engage with content.

These theories gained widespread popularity due to their appeal in explaining why some students excel in certain subjects while struggling with others. It seemed plausible that tailoring teaching methods to match an individual’s preferred style could enhance their understanding and retention of information.

In response to this growing interest in catering to diverse learning needs, many educators embraced the concept wholeheartedly. Schools began implementing strategies such as visual aids for visual learners or hands-on activities for kinesthetic learners. Teachers aimed to create differentiated lesson plans targeting specific learning styles within their classrooms.

However well-intentioned these efforts were initially thought to be, recent research has cast doubt on the effectiveness of using learning styles as a basis for instructional design. In a comprehensive review published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest, Pashler et al. (2009) found little evidence to support the idea that matching instruction to learning styles improves academic performance.

The authors concluded that while individuals may have preferences for certain types of information presentation, such as visual or auditory, these preferences do not necessarily translate into better learning outcomes when instruction is aligned with them. They argued that teaching methods should be based on evidence-based practices rather than catering to individual learning styles.

Further studies have supported this skepticism towards learning styles. One study conducted by Rogowsky et al. (2015) involved 114 undergraduate students and found no significant difference in comprehension or retention between participants who were taught according to their preferred style and those who were not.

These findings suggest that efforts to match instruction to individual learning styles might be misguided. Instead of focusing on how learners prefer material presented, teachers should consider utilizing instructional strategies backed by research and proven effective for all learners.

While it is important not to dismiss the notion of individual differences completely, it is crucial to recognize that these differences are more complex than simply categorizing individuals into specific learning styles or intelligence types. Humans are multifaceted beings whose engagement with educational content depends on various factors beyond just personal preferences.

For example, contextual factors such as the subject matter being taught can influence how an individual learns best. A student may excel at hands-on activities in science class but prefer reading and writing when studying literature. Additionally, previous knowledge and prior experiences play a significant role in shaping one’s approach to new information.

Instead of investing time and resources into tailoring instruction solely based on perceived learning styles or intelligences, educators would benefit from adopting a universal design for learning (UDL) framework. UDL promotes flexible instructional practices that accommodate diverse needs within a single lesson plan rather than targeting specific groups exclusively.

UDL recognizes three primary brain networks involved in learning: recognition networks (how we gather information), strategic networks (how we organize and plan our learning), and affective networks (how motivation and engagement impact learning). By considering these three networks, teachers can create lessons that offer multiple means of representation, action, and expression.

For example, a science teacher employing UDL might provide visual diagrams for students who benefit from visual representations while also offering hands-on experiments or group discussions to engage kinesthetic learners and enhance conceptual understanding. By utilizing diverse instructional strategies within one lesson, educators can cater to a broader range of preferences without pigeonholing learners into rigid categories.

It is important to note that the skepticism towards matching instruction with learning styles does not negate the significance of personalized education. Recognizing individual strengths, weaknesses, interests, and cultural backgrounds remains crucial for effective teaching. However, it is essential to move away from the oversimplified notion of fixed learning styles as the sole determinant of educational success.

In conclusion, while the concept of learning styles and preferences gained popularity in education circles over the past decades, recent research challenges their effectiveness as a basis for instructional design. Instead of focusing exclusively on individual preferences when tailoring instruction, educators should adopt evidence-based practices that accommodate diverse needs within a universal design for learning framework. By recognizing the complexity of human cognition and engaging learners through various means of representation, action, and expression, educators can foster inclusive environments where all students have an opportunity to thrive.

Leave a comment