Neuromyths in Education: Separating Fact from Fiction

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the relationship between neuroscience and education. Unfortunately, this has led to the emergence of several neuromyths that are not supported by scientific evidence but continue to be widely believed among educators and parents alike. These myths can have negative consequences for students’ learning outcomes and should be addressed.

Myth #1: People are either left-brained or right-brained.

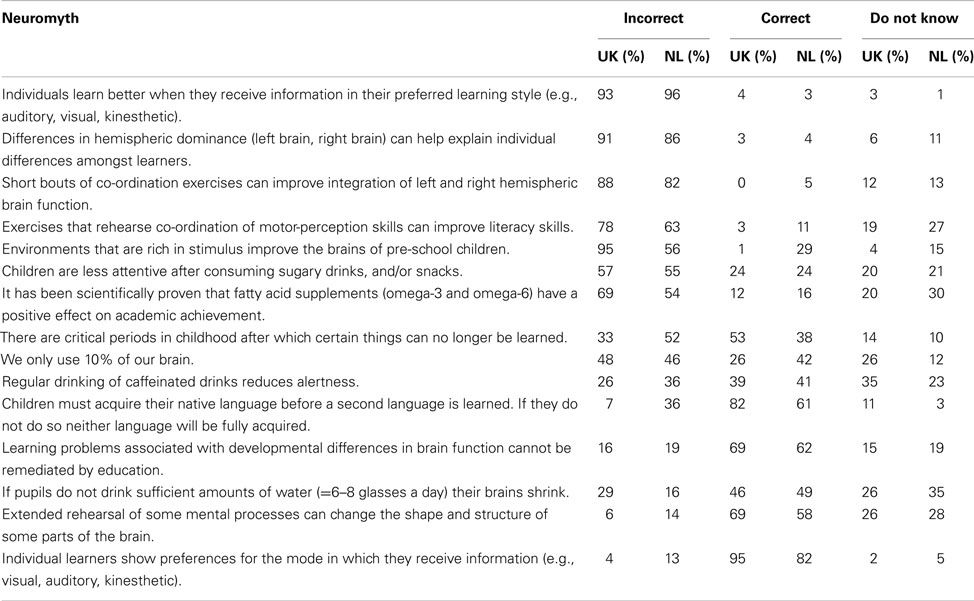

The idea that people are either left-brained or right-brained is one of the most popular neuromyths out there. The theory suggests that individuals who are more analytical and logical are left-brained, while those who are creative and intuitive are right-brained. However, research shows that brain functions don’t work this way – both hemispheres of the brain work together on all tasks.

Myth #2: Listening to classical music can boost intelligence.

The “Mozart effect” is a commonly held belief that listening to classical music can make you smarter. While it’s true that music can have an impact on mood, attention, and memory, there is no evidence linking it specifically to improved cognitive abilities.

Myth #3: Learning styles determine how we learn best.

Many people believe they have a particular “learning style,” such as visual or auditory. However, studies show that teaching methods based on learning styles do not lead to better academic performance than non-preferred methods. Instead of focusing on learning styles, teachers should use a variety of instructional strategies so students have multiple ways of approaching content.

Myth #4: We only use 10% of our brains.

This myth has been debunked time and time again – humans use all parts of their brains throughout the day for various functions like breathing, moving muscles, processing sensory information etc.

Myth #5: Brain training games improve general cognitive abilities.

There are many brain training programs and games that claim to improve general cognitive abilities like memory, attention, and problem-solving. However, research suggests that the benefits of these programs don’t transfer to other tasks or real-life situations outside of the game.

By busting these neuromyths in education, we can help ensure that teaching methods are based on accurate scientific evidence. This will ultimately lead to better learning outcomes for our children.

Leave a comment